Uruguay is where it is said the ‘old world’ meets the ‘new world’ in South America. As the term ‘new world’ is problematic, I prefer to say where European wine truly meets those of the developing world of South America. This encontrase or rendezvous of Spain, Italy and France form part of Uruguay’s fabric and is uniquely and authentically expressed in their wines.

Upon arrival at Montevideo airport, I get an immediate and unexpected sense of how it is different Uruguay is from other countries in South America as automated border control systems are in use. I know it is something you may take for granted in UK and European airports, but they are not installed in the rest of the continent, and, in part, this reflects the wealth, stability, advanced and forward-thinking nature of the country. To link it with another European country, the Switzerland of South America, if you like.

I also notice the rain and I am reminded of Galicia - twice the amount that you get in London, I read - and, true to form, for the first three days it is ‘cats & dogs’; there is definitely an extraordinarily strong Atlantic influence here.

A stupendous Montevideo storm drain versus the one right outside my house in broken Britain which has been full of leaves for over a year and has weeds growing out of it. Putting this in the public domain will make no difference to my borough council so I will either clean it out myself or move to Uruguay.

Unlike the Andes’ nations, this maritime effect delivers its fair share of stormy, leaden weather, although ‘global weirding’ has seen drier, hotter summers of late, which was brought clearly into focus this summer with a serious drought. Later in the week of my late April visit, the skies clear to an almost cloudless, dazzling bright blue colour and I don shorts and a tee, and could easily be in Bordeaux or Bilbao in the late summer.

The country is very flat. Our minibus driver, Pablo, points out the highest point in Montevideo with a mixture of pride and self-deprecating humour. My guess is that it is no more than 20 meters above sea level - a humbling thought but maybe the industry takes high altitude vineyards too seriously: after all some of the best wines in the world come from the low-lying gravelly hills of the Medoc in the Bordeaux region.

A remarkably hilly bit of Uruguay. This is Maldonado in the south-east and is looking from Bouza’s vineyards towards the Cerro del Toro vineyards (the hill of the bull) which is a whopping 253 metres above sea level and beyond this, just 2 km further, to the Atlantic Ocean.

Outside of the bustling capital city, Uruguay has a timelessness and sense of big open space, unsurprising, I suppose, as two-thirds of its 3.5 million population live in Montevideo. To compare it with the UK, which is 40% bigger in area, their population is almost 20 times smaller. With that disconnect in mind, they say that if the world ended, you could live here for another 20 years, such is the seeming remoteness of the place. I imagine in self-sufficient and bucolic bliss.

The slow pace of life in Garzon with a local pootling along with his collected wood. To be fair, he was faster than most of the traffic in London and there are no lights or any other road users there, apart from us. Is the wood for an asado perhaps? The asado or barbecue is more than just a Uruguayan tradition, it represents the country's whole identity, acting as a social linchpin, as one of the most strongly-rooted customs and as a symbol of friendship.

Towards the centre of this pear-shaped country, wild grasslands (or La Pampa) of the Gauchos-land are where herds of beef cattle, cows and sheep graze endlessly. 12 million gives Uruguay the highest number of cattle per capita in the world! Fruit orchards, olive groves and even lesser-spotted vineyards can be identified further south around Montevideo and close to the Rio de la Plata or River Plate, and towards the wild Atlantic Ocean coast. If you consider it a river and not an estuary, it is the widest in the world, slowly opening its unthinkably big mouth to 220 kilometres or 140 miles in width which, from London, would take you to the rainy Peak District or chocoholic Brugge, if you prefer.

Whilst the pace of life appears relaxed, many families still recall the tough, impecunious existence of their first-generation ancestors. There was a big wave of newly-arrived Italian and Spanish immigrants from the late 1800’s and they have established successful, small and close-knit family businesses which prevail today. They also brought with them their rich European food and wine heritage and the country’s cultural diversity is celebrated with a fun-packed 40 day long annual carnival in Montevideo.

Having enjoyed long-term political and economic stability, Uruguay has an egalitarian society and a big middle class. To contextualise this, the neighbouring wine-producing countries of Argentina (which has political and economic turmoil), Chile (where the resilience of its people is frequently tested by natural disasters) and Brazil (whose big economy has been in recovery for over a decade) have all had challenges.

Uruguay’s healthy economy gives its people the highest per capita income in Latin America. Whilst its service sector continues to grow, agriculture contributes a significant 5.6% of its GDP, compared to 0.7% in the UK.

The industry we know today, the modern wine industry, was only born back in the 1990’s when the decision was made to focus on quality, or to use the modern parlance, to ‘premiumise’ wine production. Some big-wig international wine consultants identified the potential and its international appeal, like the mouth of the River Plate, slowly began to broaden.

Tannat is the signature grape of Uruguay having been introduced by Basque immigrants, although this is disputed, and 1,600 hectares are now planted. That is 27% of the country’s total 6,000 hectares under vine. However, Tannat is a grape that originates in south-west France and is so named because it has a thick skin and 5 seeds, instead of the usual 2 or 3 of other varieties, so when it is pressed hard and then fermented it delivers wines with dark colour and abundant tannins - tannins being the operative word here for its nomenclature.

Back in Uruguay, Reinaldo de Lucca, one of the most respected winemakers in the land said, ‘We didn’t choose Tannat, Tannat chose us.’ He means, I believe, that it is very much at home there and, unlike many other grapes, it likes the humidity. This and warm summer sunshine give it perfect conditions to produce wine consistently with appealing depth of colour, black fruit aromas and flavours, balancing freshness, and plush tannins. Now lighter, more modern, concrete-aged expressions, offering greater purity, are being made and Tannat blends too along with aromatised Tannats, with terroir Tannat being perhaps the most exciting of these developments of the last few years. There is such diversity in styles now that it is difficult to affirm that Uruguayan Tannat is best in the world, but I do believe it is - if not the best, certainly the most adventurous and exciting.

Familia Deicas’s historic winery and vineyard at Establecimiento Juanicó. Santiago Deicas tells us that Uruguay supplied corned beef and leather goods to the troops during the world wars and the World War II debt owed by France resulted in the government agreeing the production of Cognac at this site. I did not know about the exception the French authorities made to their appellation controlee rules but, I guess, every day is a school day.

To claim that Tannat benefits you is controversial, especially as the blinkered modern-day temperance movement centres its discussions narrowly on the issue of health, whilst neglecting some of the other positive aspects of wine - the cultural, gastronomic and social aspects. Fact-check this: Tannat has 3 times more resveratrol, an antioxidant associated with cardiovascular health benefits, than other Bordeaux varieties but let’s not go down the ‘French paradox’ rabbit hole here. Instead, let’s turn to other grapes that are successful in Uruguay.

Albariño has been coined the star white grape of Uruguay and for good reason. It reaches far beyond the Galician family heritage of growers, having a natural affinity to the maritime climate and terroir and reflecting a much more European character than its neighbouring countries by displaying a savouriness, a beautiful gastronomic acid frame and moderate alcohol.

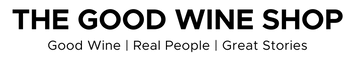

Recently I was asked by a colleague how they differ from those of Rias Baixas in Galicia and lamely, l confessed to them being similar, sharing that Atlantic coastal freshness and salinity, and sometimes having a riper fruit profile. Although the first plantings in the country were as recently as 2001, it has come a very long way and in the last decade, an exciting area has emerged and is producing some world-beating Albariños. Maldonado is in the south-east of the country, just over an hour’s drive east of Montevideo. Morning fogs and afternoon sea breezes dry the humid coastal air and the ample sunshine and gently undulating rocky hills offer up free-draining decomposed granitic soils that provide perfect conditions for this variety. All of which has Amanda Barnes, our English-born, stage 3 Master of Wine student, Uruguayan wine guru and guide for the week, claiming rapturously that it a ‘hotspot’ for top quality Albariño. As I taste my way through many Albariños, wondering why I would ever doubt Amanda’s local and superior knowledge, I discover that she is absolutely right, of course.

There are also other varieties that show great promise, not least Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, but so little is planted and not much makes the long sea voyage to the UK. Over the coming years do watch this space.

So, back to wines that you can lay your hands on. Here are 3 categories of must-tries:

1. The ground-breaking

Vina Progreso is the brainchild of the young, experimental Gabriel Pisano, who is based at his uncle’s, Daniel Pisano, winery in Progreso, so named as the railway arrived in 1871 though it is just 25km due north of Montevideo. They have Ligurian and Basque ancestry, but the extended family feels more strongly routed in Italy. Daniel adds to the mix that they have Burgundian soil – clay with limestone – and the climate of Bordeaux.

Gabby created Bodega Experimental unexpectedly after he persuaded his uncle to take a bottle to a Quebec wine fair just to get some feedback and the buyer of the state-controlled board loved it and bought the lot. Gabby has continued making small quantities of minimal intervention wine using the ‘Underground’ label. Keeping it in the family, Gabby uses his aunt’s magical drawing for the labels, partly as it was to hand and because the imagery is outstanding.

Third generation, young gun Gabby, talking us through his hands-off approach in the barrel store at Pisano. I am just so glad he has increased quantities a tad so we can get our mitts on some and it does not all go to those thirsty Canadians, though we do have one in our midst.

Gabby’s Pet Nat Torrontes 2022 also stands out. Discover the magic that Gab conjures up in what is only his second vintage after all. Made, he says, with zero intervention, expect a slight haze, floral aromatics, a gentle fizziness and a light spicy textured note. This talented young winemaker is on a roll as his Pet Nat 2023 won the best sparkling wine in Tim Atkin’s recently released Uruguay 2024 special report.

2. The terroirist

Just 2 km further north, but in the Juanico region, lies Familia Deicas which I referenced earlier. It is a great place to get an overview of Uruguayan wines as, having ambitiously expanded in the last 20 years, they now own vineyards across 5 districts. Santiago chased forests, wind, which he says is more important than altitude, and good terroir to identify sites for new plantings. Santi, who is also a third-generation winemaker of Italian descent, has a science background having trained as a food engineer. He qualified as a winemaker in Bordeaux and is deep thinking, erudite and engaging.

This is just part of the terroir-obsessive Santi’s bore hole collection showing the cross section of topsoil and mother rock in different vineyard sites - I was disappointed Santi did not allow me inside the case to lick the rocks though - and a delightful and moving homage to Santi’s great-great grandfather, Massimo Dei Cas, who arrived from Valtelina in Alto Piemonte to Montevideo in 1928.

Uruguayan’s national pastimes include sharing a mate (not what you may think), the asado (a next level barbeque) and watching the sunset - all three in the same evening sometimes. Pictured is the smiley Santi Deicas sharing a mate, the national drink - a little like tea in blighty. It is a caffeine-rich brew of yerba leaves which, like tea, you pour hot water over. You sip it from the metal straw, or traditionally from a cow horn and then pass it around the group of people you are with as a symbol of friendship and equality. I tried it and it is like herbal matcha on steroids: somewhat off-the-charts bitterness for a super taster I imagine.

Even the most sceptic or price sensitive drinker should dip a toe in the water with Santi’s Tannat sur Altlantida. It is a blend from 3 different areas, Juanicó, Garzón and Mahoma on a mix of soils: clay and limestone, granite and schist. It is given short warm maceration to extract dark colour and plentiful plump plummy and ripe blackberry flavours and plush tannins making this the gateway to further exploration.

Not content with running a successful family winery, Santi recently started a collaborative side-project called Bizarra Extravaganza, born out of a desire to innovate and apply his craft beer-making techniques to make natural wine. Made in tiny quantities, of around 2,000 bottles each, they are quickly becoming some of the most sought-after vanguard wines from Uruguay. Here they have progressed to apply coffee making methods to Tannat with the Tannat Espresso and Tannat Cold Brew. Try these two jaw-droppingly good wines side by side whilst you can; I know which I like best. What will you think?

3. The Italianate

About an hour’s drive to the east of Montevideo, along the coast and in the Atlántida sub region of Canelones, we arrive at Pablo Fallabrino’s modest winery which is surrounded by his 20 hectares of vineyards. Pablo’s focus is on Italian varietals and methods of production. His 2 hectares of Traminer Aromatico, a grape of Tyrolean origin, represents nearly all of the plantings in Uruguay. Pablo also has most of the plantings of Barbera, Nebbiolo and Arneis in the country and he is about to plant a little experimental row or two of Cortese and Freisa. It is no surprise, then, that Pablo has Italian roots, his grandfather Angelo having arrived from Piemonte in 1923.

Pablo is a pragmatist, laid-back and feisty, a plain-speaking maverick whose blonde locks and ponytail are perfectly suited to his love of surfing. Here he is telling us how the proximity to the ocean (just 4km away) cools his vineyards but, actually, I think he is practising one of his surf tricks: I have researched some moves, and it looks like a snap to me. Plus, you cannot see the surfboard he is standing on and corded to his ankle.

Pablo’s vineyards can get very cold and he regularly experiences potentially damaging late spring frosts which is highly unusual in Uruguay, even in the coldest of winters, as it is generally mild. He says he easily remembers the dates they usually occur, 12 October and 2 November in most years, as this coincides with public holidays, so his days out on the waves are cut short. The strong onshore wind is called the Corriente de Las Malvinas (the Falklands stream) and not only fans the breaks for surfers but messes with Pablo hair. The air is so pure and clean, and sunshine so bright and warm, it is worth being outside in the gale. He adds that it is a clean environment and just beyond the vineyard is a nature reserve, full of native grasses, a big lake and over 200 bird species (of the 450 identified in the country). Afterall, Uruguay means the river of the painted birds. It is well worth cloaking the vines with netting just prior to harvest to stop the many birds gorging on grapes.

Three of his wines wowed me on my visit. El Elefante Pisador 2023 is a skin-contact or orange wine with the Traminer spending a week on skins. The retro elephant pressing the grapes label comes from a calendar his dad had in the winery that he remembers when growing up.

The Barbera Especial 2022 has classic red and black cherry flavours that are juicily ripe and so very, very tasty. Adrian, our Italian specialist who is based in the Chiswick shop, recently described it as "The ultimate meat-feast pizza pairing" and having tried it, he is so right.

Whilst banging on about Italy, I return to Tannat, here made in a ‘ripasso’ style with a thrilling Italian twist. Pablo says he copied this cordon-cut method of semi-drying the grapes from a grower in Valtelina. It is made as a tribute to his grandfather, Angel, and what a fitting homage. 15 days of drying offer the Angel’s Cuvee a seductive warm stewed plum and a fig jam high, all balanced with a scratch of sandiness and earthy truffle oil.

To conclude, one of the learnings from my visit is that there is such diversity of Tannat and I hope the above illustrates that well, after all (cat lovers tune out for two seconds) there is more than one way to skin a cat.

Do check out Albariño as it is the best in the world, outside of Galicia.

The Maldonado region is an emerging, super exciting place to be and shows great potential.

Whilst the modern scene is in its adolescence, there are several highly talented, next generation winemakers rewriting the rule book and breaking new ground.

Off the radar, undiscovered gems are there for the taking so join an orderly British queue and panic buy away.