This month, we’re delving into the world of Grower Champagne, and making an incredible selection available to you to explore, enjoy and celebrate with. Finally, there is actually something to celebrate!

I wanted to share a bit of history and discuss the differing approaches that big brands in Champagne have in comparison to the smaller grower-producers who are dotted across the region.

The rise of brands in Champagne

Champagne has always been reliant on merchant houses, due to the success of its wines in the courts of Paris in the 17th and 18th centuries in particular. The region’s proximity to the capital allowed far easier access than did areas further south (until the introduction of a railway linking Paris to the South of France).

This meant that Champagne was historically the go-to and made wines of all styles. It was far easier for a merchant to source widely and buy grapes from growers to offer a larger portfolio of products to be consumed by the courts and nobles. These merchants traded off their names, leading to Champagne’s early adoption of brands.

Desire for sparkling wine increased the prominence of these merchant names, and over time, they could cater for a broad range of tastes by altering the wines’ sweetness with what is known as dosage (Brut nature, Extra Brut, Brut, Extra Dry, Sec, Demi-Sec). Then began the discovery of creating consistent styles year on year by fractionally blending vintages and different grape varieties from year to year.

The Champagne Riots and development of classification systems

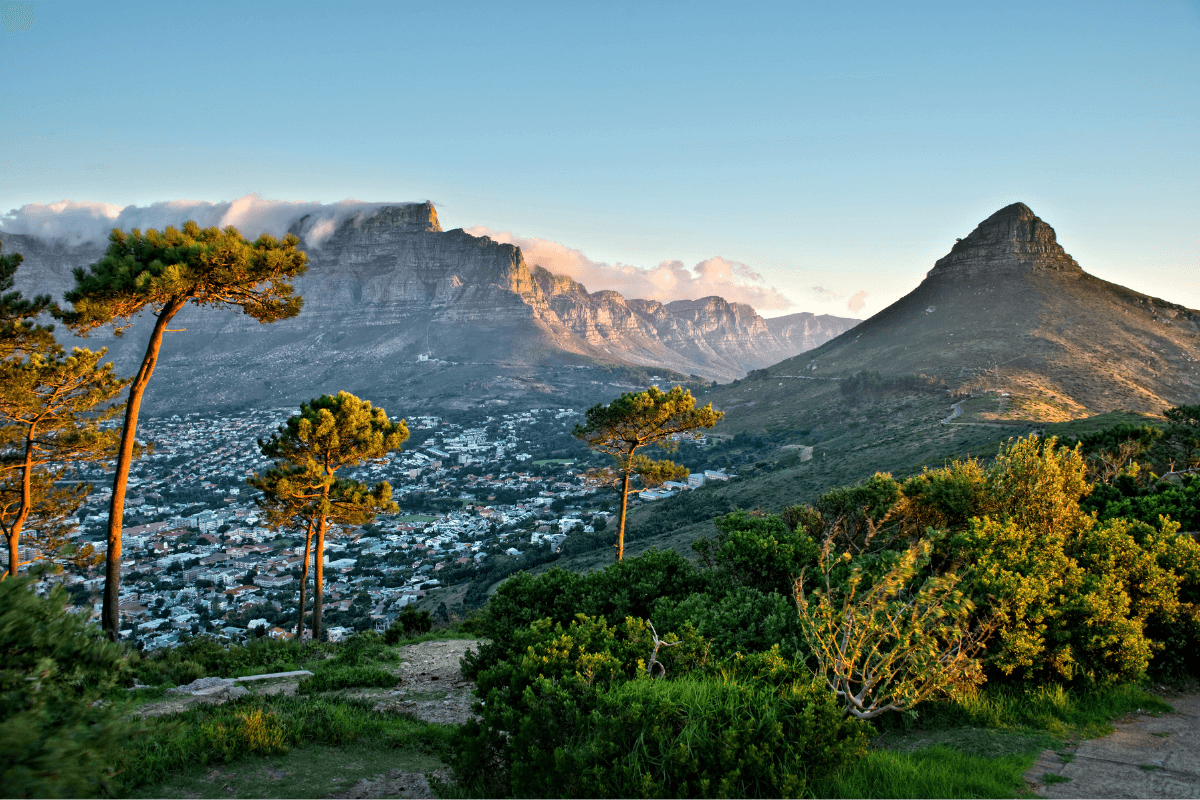

The introduction of railways to France throughout the 19th century opened the wine market, making many other regions more accessible, increasing competition in France’s capital. Merchants were also able to source wines from further afield at cheaper prices than those they could acquire from the local growers, and since the Champagne name wasn’t protected, they could still label it as Champagne.

Champagne growers were being outcompeted, and the amount they could charge for their grapes slumped dramatically. Their discontent boiled over in 1910, following an awful vintage that saw all but 4% of crops decimated by bad weather. Merchants became more overt with their trading of grapes and wines from outside the region to compromise for the poor local harvest. Major riots sprung up throughout the Marne Province, the hub of Champagne production.

Champagne Riots

World War I put an end to the discontent, and after the war, new boundaries were formalised, and a classification system was introduced to ensure fair pricing for grapes across the region.

This includes the Echelle des Crus. Which is a system whereby the quality of vineyards around villages dotted across the region has been rated with a score of between 80 and 100%. In total, there are 318 villages that have been ranked. 257 rank between 80 and 89%. 44 are ranked between 90 and 99% - the Premier Cru sites. 17 are ranked 100% - the Grand Cru sites. The higher the rating, the more a grower can charge for their fruit. There are representative bodies for both the merchant houses (Grands Marques) and the growers, who sit down together each year and discuss how prices will be fixed, and what the harvest yields will be. Supply and demand are closely analysed to determine the maximum permitted levels of production.

COVID

This is a product that has always marketed on success and celebration. There hasn’t been much worth celebrating over the last couple of years… As you can guess, COVID has had a huge impact on demand for Champagne. Sales have plummeted. This has led to some tense discussions regarding how much fruit can be harvested. The big houses favour smaller quantities. They have the capital and the means to get through a year or two where the scale of production is lower than average. Growers and grower/producers need to sell as much as they can to get by and thrive in a challenging environment, particularly since the cost of land is prohibitively high, meaning they can’t scale up production so easily, and must settle for what they already have and make the most of it.

There is a lot of contention around this. The age-old tension between the two facets of the industry has risen back to the surface and has highlighted the power that the big brands laud over the machinations of the region.

Differing approaches to production

The Grandes Marques

They typically own little to no vineyard land, relying on sourcing fruit from growers. They have the flexibility to source fruit from across the region, and often make Premier and Grand Cru wines from fruit acquired from many different Premier and Grand Cru villages, not just one.

They have a long heritage of wine making in the region, and therefore have an extensive selection of reserve wine that they can utilise in their non-vintage cuvees. This allows them to produce a house style that is so consistent year-on-year that consumers can reliably buy the style they know and like without any qualms about vintage variation.

To give context, Moet & Chandon produce 30 million bottles per year. They own approximately 1,684 hectares of land which, whilst extensive, only accounts for 1/3 of the grapes needed to produce such quantities. They source from approximately 4,000 more hectares overall. Growers are focussed on producing as close to the maximum permitted yield as possible, and so agrochemicals are widely used to facilitate this. These yields are incredibly high – at around 100 hectolitres per hectare, with yet more allowed to accommodate for reserve wines. To put this in context, in the UK between 2013 and 2017, average yields were around 24 hectolitres per hectare – less than a quarter the yields of Champagne!

Dosage (the addition of grape sugar before corking and releasing the wine) is widely used and is a key component in achieving a consistent style year on year. ‘Brut’ is the most common term that you will see on a label, which allows 6-12g per litre of residual sugar.

Moet & Chandon’s product placement focussing on celebrity lifestyle to enhance the aspirational feel of the brand

Grower Producers

They own their own production. They use only grapes from their own vineyard holdings, which are typically tiny. They are more focussed on conveying a sense of place – this idea of terroir into their wines, often vinifying tiny quantities of wine from individual plots to highlight the different characteristics the grapes express from the varied conditions in which they are grown.

They are not interested in producing wines with consistent flavour profiles each year, they are more focussed on producing wines that express the conditions of that year, that are balanced and characterful.

An example of a Grower-Producer’s approach to making Champagne would be that of Cédric Bouchard. He operates out of the Côte des Bar in the south of Champagne, with a focus on Pinot Noir, although he does have a couple of limited release Blanc de Blancs made from 100% Chardonnay, and 100% Pinot Blanc. He owns a mere 3.5 hectares of vines. He doesn’t use any agrochemicals and encourages biodiversity amongst his vines. His whole ethos is focussed upon creating wines from a single vintage, single vineyard, and a single variety. He makes wines with less pressure, giving a softer, more textural mousse. The typical aim is for around 6-bars of pressure. His often hover around the 5-bar mark, often slightly less. He uses no dosage at all, making wines that are Brut Nature. His yields are amongst the lowest in Champagne, averaging around 25 hectolitres per hectare.

It must be said that one of the greatest hardships regarding Grower Producers is the inconsistency amongst them. Many are outstanding and incredibly talented, but there are quite a few who produce wines that are well below the region’s standard.

Cédric Bouchard amongst his vines on a winter's morning

Identifying Champagnes at-a-glance

Initials |

What they mean |

Brief description |

|

NM |

Négociant-Manipulant |

Houses that buy in grapes and wine. Responsible for most of the Champagne produced. |

|

RM |

Récoltant-Manipulant |

A grower who makes Champagne from their own holdings. |

|

CM |

Coopérative-Manipulant |

Co-operatives take in grapes from growers and either sell them on to big houses or make wines themselves. Responsible for Private label production (e.g. Tesco own label). |

|

RC |

Récoltant Coopérateur |

A grower who is a member of a Co-op, who buys back wine from them to sell under their own label. |

How to identify these letters on the label: Négociant-Manipulant

How to identify these letters on the label: Récoltant-Manipulant

We’ve collated an incredible list of some of Champagne’s most accomplished growers and have an incredible array of styles to try and enjoy. The joy of Grower Champagnes is that despite their extremely limited production, they sit at incredibly fair prices in comparison to some of the better- known Champagne brands. It is finally time to restart and celebrate. Restart with a fresh perspective to the world’s most famous sparkling wine region and celebrate with a good glass of something made by a talented independent vigneron!