How English wine found its fizz

For Easter, we participated in the Big English Wine Easter campaign, to support the UK wine industry and hospitality so I thought this presented the perfect opportunity to talk a bit about English Sparkling wine and its origins.

Having studied at Plumpton College, I was in the heart of the industry. The College specialises in agricultural courses and offers two wine degree courses – one in production and one in business. They have their own winery and produce their own wines, almost all the leading lights in English wine production have been through the doors at some point!

Being there, I got a great inside view to the growing industry, from a tough year in 2017 (April frost, high rainfall), to one of the best in 2018 (warm and dry, long dry autumn period). This really denotes the challenging environment the industry faces.

To give context, I am going to be referring to Champagne a fair amount, because English wine is made in the same way, with pretty much the same grape varieties, often on the same soils! In fact, the potential of England for sparkling wine production has not gone unnoticed by Champagne, with many big names such as Tattinger and Pommery buying up parcels of land in Sussex and Kent to make their own English fizz.

I want to talk to you about the origins of English wine, and the beginnings of sparkling wine production. I will also highlight just how challenging the environment is, and what goes in to making the amazing wines being produced.

History

Wine production began with the Romans but is not well documented. What is certain is that wines were being grown for wine production on quite a large scale from the middle ages, around the time of the Norman conquest by monasteries for religious ceremonies. With the Domesday survey in the 11th century, there were 139 vineyards across England and Wales. The number of vineyards subsequently declined, probably due to adverse changes to the climate, the dissolution of the monasteries, and the planting of more important crops.

Fast forward to the early 20th century, between the end of the 1st World War to shortly after the 2nd World War, all commercial production of any kind stopped, leaving a gap of about 25 years, before anyone started toying with the idea again.

Ray Barrington Brock, a research chemist, began experimenting with grape varieties, determining which would ripen well in the UK's challenging climate. People like Ray inspired others to try, including Major General Sir Guy Salisbury-Jones who planted a vineyard in Hambledon, not far from Portsmouth. 4,000 vines were planted on a 1.5-acre site in 1952. In 1955, the first commercial wine since World War One was released.

Ray Barrington Brock

Since then, English wine has been through a big boom up until the 90s, when things fell flat for a period. Most who established vineyards had little knowledge of wine production, site selection, or making a winery financially productive. There is a long standing saying that 'the way to make a small fortune is to have a large fortune and buy an English vineyard'.

In more recent times, wine producers have become more conscious of the vine varieties, sites and exposures that are best suited for wine grape growing and production. They have also a better grasp on the technological and scientific necessities to help work in such marginal conditions and maximise on quality and balance in the wines being made.

Up until the late 90s, sparkling wine production was virtually unheard of in the UK, and most vineyards were planted to Germanic hybrids such as Seyval Blanc, Müller-Thurgau and Rondo. Many, due to the poor conditions they were using to grow the vines, were making insipid, low quality still wines with these varieties that are not at all popular for quality production in Europe.

Things began to change when in 1988, an American couple, Stuart and Sandy Moss, planted the Champagne varieties Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Pinot Meunier, drawing on the similarities in soils and aspects to a parcel of land nestled in Sussex, with green sand and chalk bedrock. They set their sights on traditional method sparkling wine production, and by the late 90s, their sparkling wines started winning critical acclaim. This made other producers sit up and take notice. Since then, vineyard plantings have increased exponentially, along with the number of producers all focussed on producing quality sparkling wine to rival those of Champagne.

Black Chalk Vineyards

Climate

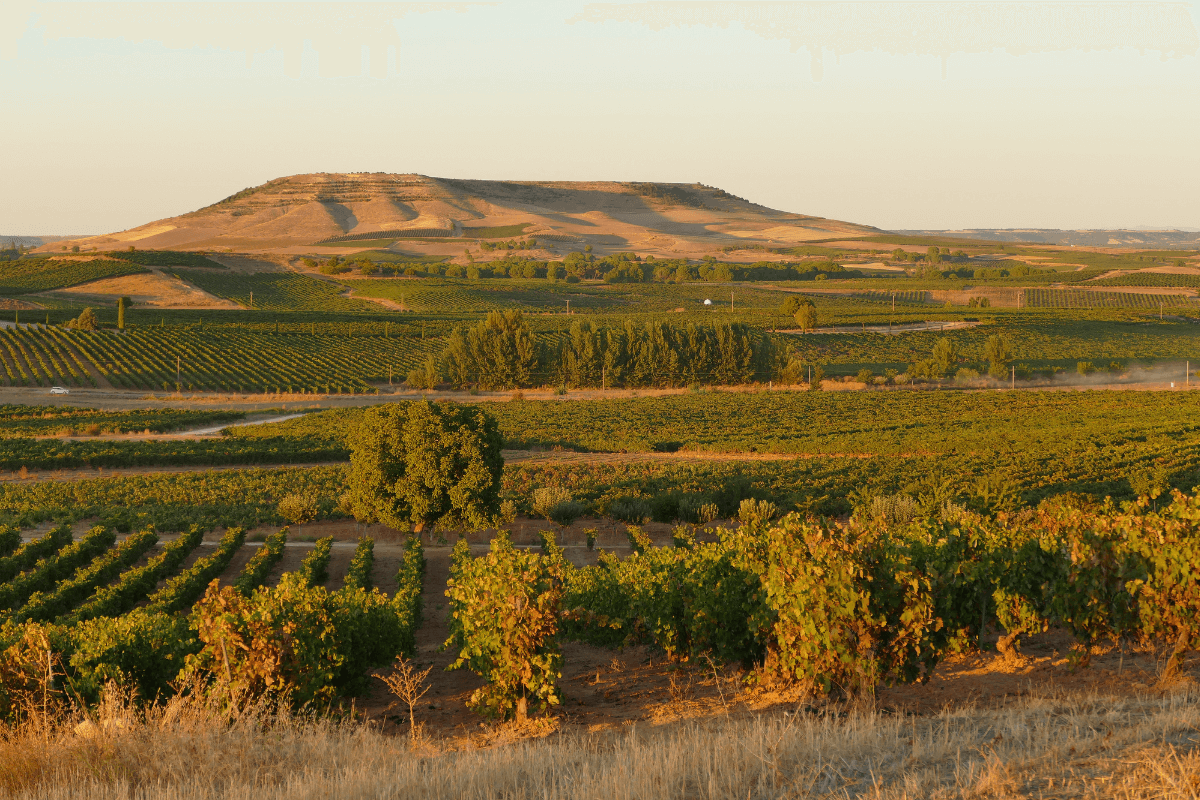

The main difference between Champagne and the UK is the climatic conditions, with Champagne being more continental, with little to no maritime influence, and sitting at a slightly more southerly latitude. The South East of the UK, where most production takes place, sits at 51 degrees, where 50 degrees is seen as the most marginal of conditions for wine production. Champagne's Northernmost reaches sit 2 degrees further south by comparison.

The maritime influence mediates the UK's climate well enough to make viticulture possible. The problems that this also brings make it a real challenge though, with only an average of 2 years out of 10 being good enough to be deemed exceptional for wine production. 4 years are deemed to be average, and 4 poor to terrible. Storms, unpredictable rainfall throughout the growing season and significant cloud cover all affect how well vines can grow.

Champagne, being more continental, has a larger diurnal range, meaning that during the growing season, daytime temperatures are generally quite warm, and night temperatures are significantly cooler, giving grapes a better chance of ripening with balance. The region is however prone to late spring frosts and hailstorms. The vines do see significantly more sun though, with continental conditions reducing cloud cover over the growing season, and weather generally being more settled.

Production

The damp conditions in the UK make vine diseases, rot, and mildew major concerns for producers, and mean that generally yields are dramatically lower than those of Champagne. Champagne limits yields each year according to supply and demand. In the UK, producers are striving to increase yields. In some years, the UK is operating on half the yields obtained in Champagne. This adds significantly to the cost of production. Lower yields = less wine to sell, so less revenue. Champagne is well established, and has an incredible marketing machine behind it. And to give you an idea of scale, in its best year ever, the UK produced 13.11 million bottles of wine (2018) while Champagne producer Moët & Chandon alone produced 30 million bottles in that same year!

Establishing a vineyard

A great example of how long it takes to start releasing traditional method sparkling wine from scratch is Rathfinny wine estate in Sussex.

They started the project in 2010, when planting new vines in the South Downs. It took them 6 years to propagate the vines and acquire fruit of a good enough quality and quantity to produce the first base wines. It then took a further two years of maturation in the bottle before releasing the first batch, and quantities were so small in that first year, it all went on allocation. It wasn't until 2020 that significant quantities started to be produced. That's ten years with little to no revenue from the crop! On top of this, wineries must invest in bottling lines, presses and high-tech temperature- controlled vats – the cost of such equipment runs in to the hundreds of thousands.

The freshness of the industry, and the lack of current infrastructure to ease costs of production mean that producing these wines in the UK is incredibly expensive. Most producers are still only managing to break even and many are operating at a loss.

Rathfinny Wine Estate

Quality today

There is no doubting the quality of wine now being produced, and their success in global wine competitions and blind tastings testifies to the industry's amazing potential in the years to come. Do not be frightened by the price point. These truly are serious wines that rival some of the best in Champagne! When considering everything that producers face when growing and making their wines, they should even be selling for more.

One word of caution

Do not be drawn in by supermarket labelled 'British wine', these are wines made in the UK from grapes or must imported from other countries. These wines sell at cheap prices and are of poor quality. Furthermore, they have nothing to do with English wine!!

There is much to be proud of with our local industry, and much to celebrate too, so raise a glass of the good stuff this weekend and have a Happy Easter!