Most of Europe’s classic wine regions owe their existence to a combination of geological hiccups, political intervention, disaster, history and the need to trade - in no particular order. Whatever the colour, taste and feel of the wine in your mouth, it is just the top-most bit of a pyramid -the sum of all the factors that produced it -not just the winemaking…

For me this is very much where my joy of wine lies - almost as much as the sensory pleasure of drinking it!

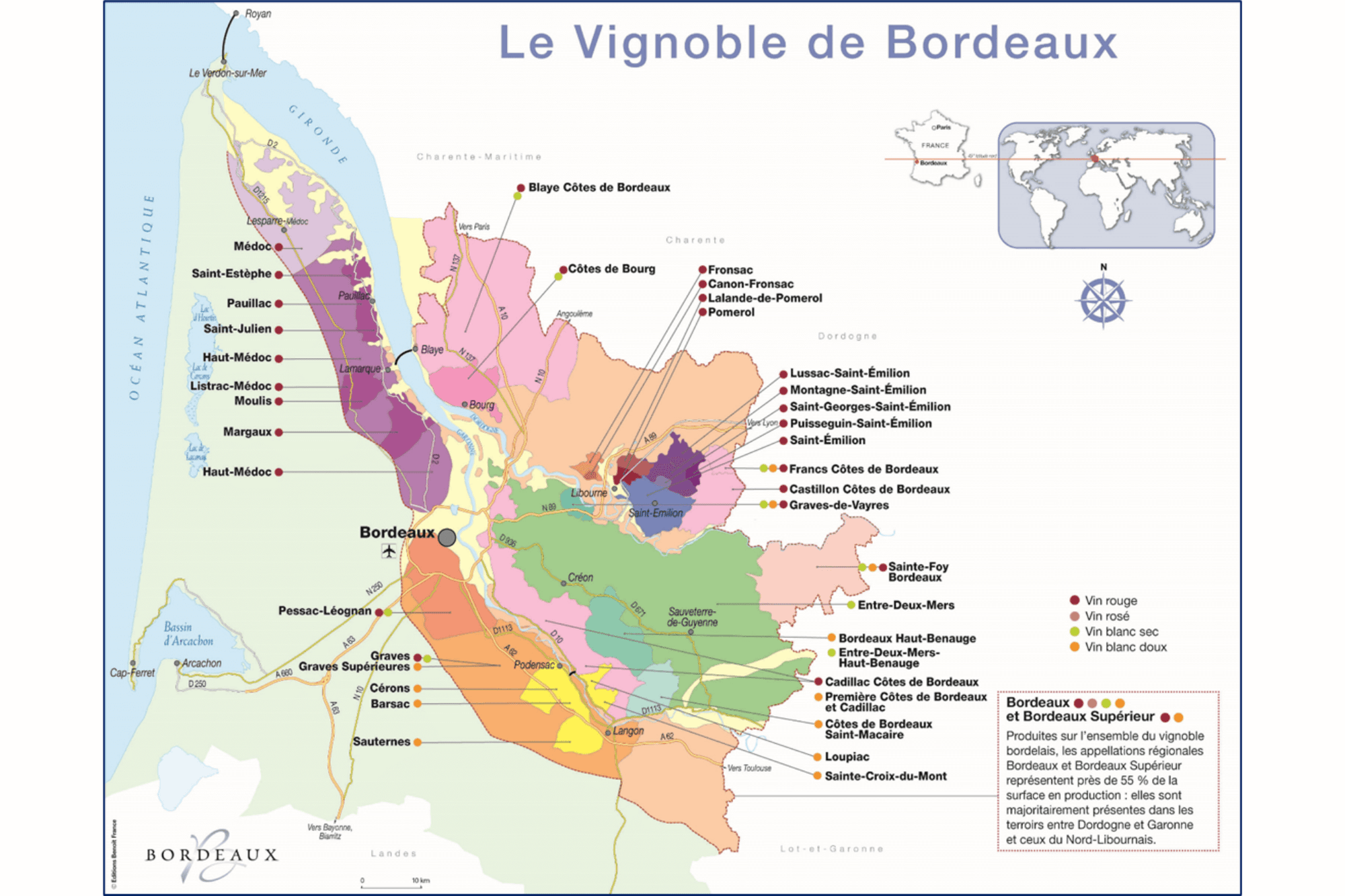

Bordeaux is bisected - and then trisected by rivers. From the estuary the mighty Gironde River flows down to a point just north of Margaux. As you look at the map of Bordeaux you see that the river then divides into the Garonne, flowing to the left down past the city of Bordeaux to the Graves and, on the right, into the Dordogne flowing off toward the east.

The large green region sandwiched between the two rivers is Entre Deux Mers - historically home to white grapes, but for the last 40 years planted mostly to Merlot and home to much of the best value Bordeaux to be had.

But it’s the Banks, the Left and the Right, that really define a certain style of red associated with each one. So what’s behind such an apparently simplistic definition? The most striking difference is in the grapes. On the left bank Cabernet Sauvignon dominates -on the right bank Merlot does. This is not accidental- there are differences in climate and soil which favour one rather than other.

The Left bank climate is slightly cooler as it’s closer to the Atlantic, and while there are some Pine forests to the west which provide a bit of shelter, it’s decidedly less balmy. Soils here, particularly those close to the river are gravel. In fact the whole of the North Medoc was marshland until the Dutch drained it at the end of the 17th century - so we owe them for giving us the joys of Paulliac, Saint-Julien and St- Estephe.

Cabernet Sauvignon is a late ripening grape -it starts growing later and really does depend on a warm, late summer to ripen well. Gravel soils soak up the day’s heat and release it over the night keeping the vineyard warmer. It’s also very free draining -something that encourages the vines to root more deeply. So a typical Left bank red blend would be 65% Cabernet Sauvignon, 30% Merlot and the rest Cabernet Franc, Malbec or Petit Verdot. Cabernet flourishes here because the climate is slightly cooler, the ripening season longer and it’s very happy on warmer gravel soil.

On the right bank the gravel disappears, giving way to sticky clay with a bluish tinge. Merlot flourishes in the cold clay soils here. Here and there are parcels of limestone where Cabernet Franc is traditionally planted. The Right bank is a little drier and warmer - a bit more sheltered from the Atlantic weather. Merlot ripens earlier and while the cooler soil slows things a little, as the climate warms it’s becoming harder to manage ripening without excessive sugar levels. Here the proportions of the left Bank norm are inverted to 60% to 80% Merlot and the balance is more likely to be Cabernet Franc than Cabernet Sauvignon.

So if you were to describe how these different proportions of grapes translate into distinctive styles so representative of their respective origins this would be a very basic guide:

Left bank reds reflect the higher percentage of Cabernet Sauvignon in wines with higher acidity and a more dark than red fruit character. Blackcurrant or Cassis, as the French would call it, is often mentioned. Pencil or graphite notes are sometimes referred to and cedar and leather in mature wines. Cabernet’s assertive tannins also mark the texture which is typically much less fleshy than Merlot dominated wines. Alcohol levels tend to be a bit lower too.

Right bank reds reflect the higher level of Merlot with its softer, plusher mouthfeel , plummy fruit and lower acidity. Alcohol levels can be higher in Merlot dominant wines and this adds to the smooth sensation in the mouth.

But this is a very simplistic way of describing a process where the nuances of blending not just Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot but all the other Bordeaux varieties, plus variations in wine making techniques and vintages can give so many varied outcomes .

It’s often the case that a vintage may favour the left bank if there’s a late warm summer or the right bank if there isn’t. A late spring frost can damage Merlot because it starts growing earlier and will likely have buds already when frost strikes, while Cabernet will escape as it won’t have started growing for long enough to be at a vulnerable stage.

What does the future hold for Bordeaux?

Climate change is a real threat as recent wild fires in the south west attest, and, as summer temperatures regularly hit the high 30s or top 40 degrees, ripening or rather over -ripening Merlot is becoming more of an issue. To counteract this, Bordeaux recently approved new varieties to help future -proof production. Amongst them were Albarino for whites and Touriga Nacional, the principal red grape for Port production in the hot and drought -prone Douro Valley.

Vineyard practice is changing too – once upon a time people would strip away leaves in the vine canopy to allow sunlight in. Now the canopies are more likely to provide shade from that sunlight.

As growers re -plant a small percentage of their vineyard annually to maintain average vine age around 35 years, so they are re -planting their former Merlot plots with Cabernet Franc, Malbec or Petit Verdot- all of which have higher acidity and longer ripening cycles.

Malbec and Petit Verdot were always regarded as very difficult to ripen -no longer. On my last visit in June 22 we tasted a very lovely 100% Petit Verdot in Fronsac near Saint Emilion.

So we are already witnessing change in one of the most venerable and apparently traditional of all wine regions.

We’d be quite wrong to regard Bordeaux as old-fashioned anymore – and we’d miss out on some wonderful wines .

Bag a Bordeaux !